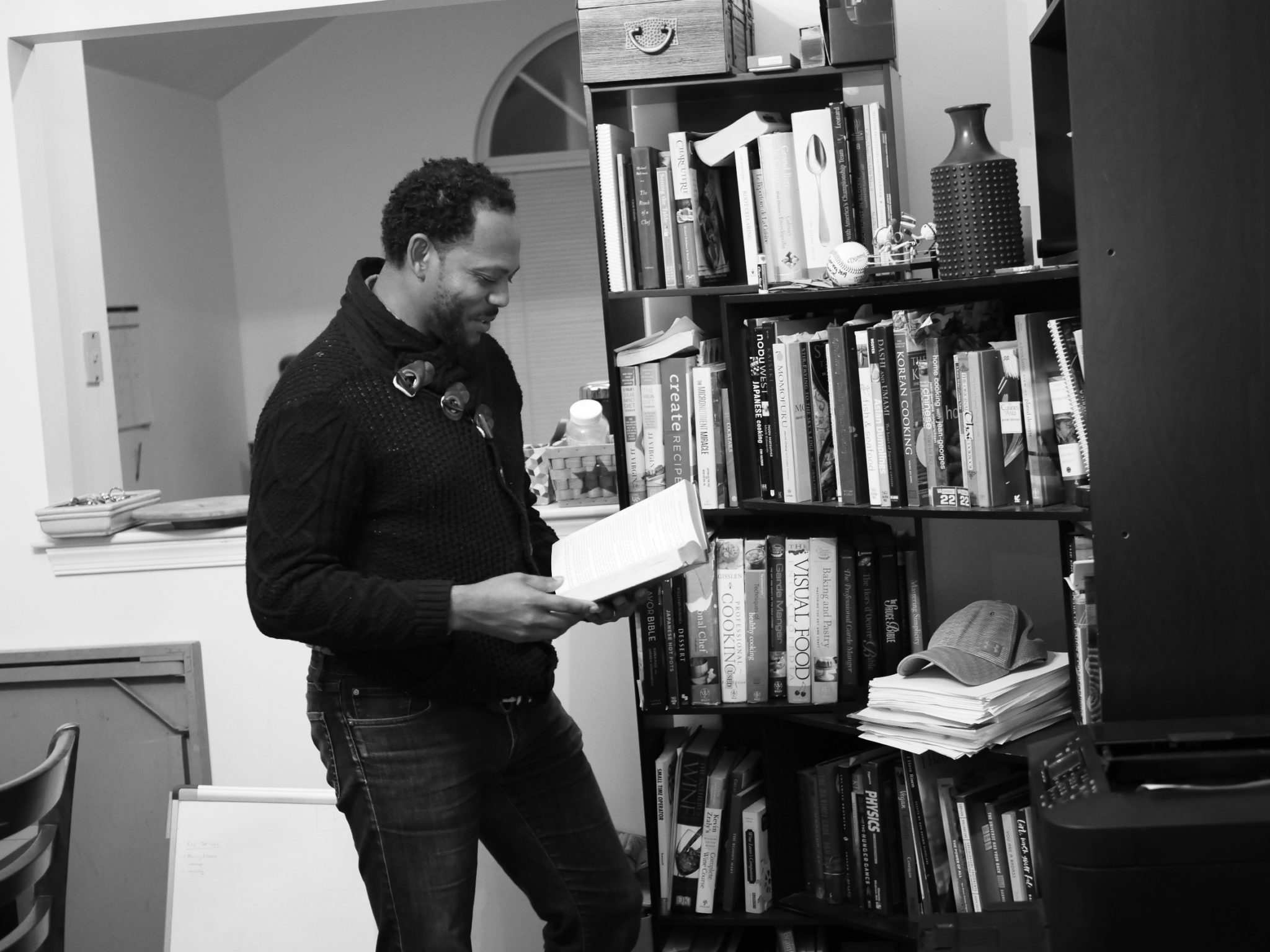

Antwon Brinson is a rising star in Charlottesville.

The chef and entrepreneur left his position running the kitchen at Common House to launch Culinary Concepts in 2018. The business helps low-income residents turn cooking into a career. Brinson went from passing out flyers to a waitlist of more than 50 names for his classes and has big plans for the coming years, he said.

But even Brinson — who can be seen at the center of a vortex of hugs and greetings in a busy room — experiences the lack of affordable housing in the Charlottesville area.

Brinson lives in Forest Lakes South with his wife and two children, but they are planning to move to Scottsville to buy a house, where the cost of living fits better into their budget.

“We love it out here, but the houses, especially in this neighborhood, start at half a mil,” Brinson said.

Roughly 17,000 families are paying more than they can afford to rent or own a home in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. The crisis touches families across a wide range of incomes, from families that rely on a minimum wage job to households securely in the middle class.

Both Charlottesville and Albemarle are working on new housing policies to address the lack of affordability in the area. Understanding the concept of area median income is key to figuring out whether those policies will work — and for whom.

What is area median income?

Key points

- Area median income means that half of the families in an area make less than the median income and half make more.

- area: Charlottesville and Albemarle, Greene, Nelson and Fluvanna counties

- median income: $89,600 a year in 2018

- used to target affordable housing resources and policies to families at different income levels

Half of the families in Charlottesville, Albemarle and surrounding counties make less than $89,000 a year, and half make more. This approximate middle is called area median income.

Anita Morrison, Partner for Economic Solutions principal, wrote the housing needs assessments for Charlottesville and the central Virginia region in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The key conclusions about who is affected by the housing shortage are described in terms of percentages of AMI.

“We use a percentage of the area median family income to stratify incomes so that we can distinguish between different groups of residents and the problems that they’re facing,” Morrison said.

Morrison said that the median is better than other types of averages that can be skewed by a few very rich or very poor people.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development provides annual median incomes for each area and defines cut-offs for various programs based on how family incomes line up against the AMI.

The department factors family size into the calculations. For example, HUD defines extremely low-income as around 30% AMI and below. This could mean a single person earning $17,950 or a family of eight earning $42,000. HUD often groups multiple cities and counties together. The counties of Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene and Nelson fall under the Charlottesville metropolitan area and have the same official AMI.

These counties are grouped together based on commuting patterns, largely to job centers within Charlottesville.

“Often, that’s the market in some sense, because what you can charge is affected by what rents are elsewhere in the region,” Morrison said.

The highest median incomes in Virginia are in the Washington region because of the concentration of high-paying jobs there. Morrison said that the Charlottesville area has a higher AMI than other parts of the state because of the presence of the University of Virginia and the appeal of the area.

There is variation within the Charlottesville metropolitan area, including pockets of poverty in the rural areas and subsidized housing within the city. When analyzed separately, Albemarle has the highest median income. Morrison said that this is partially because of the ring of newer housing in subdivisions around the border with Charlottesville.

Homeownership is generally much cheaper in rural areas, but the cost of driving can tip that balance. Commuting from Scottsville would cost around $441 a month, according to Morrison’s central Virginia housing needs assessment.

Key points

- Where a family’s income falls on the income spectrum depends on the number of people in the household.

- The area in AMI is chosen based on commuting patterns.

- AMI matters for who qualifies for what housing programs.

Despite internal variations, many housing programs use AMI percentages to determine who qualifies throughout the region.

Public housing is targeted at families making less than 30% AMI. One of the most common federal subsidies for new housing — low-income housing tax credits — was designed for families making 50-60% AMI. Many first-time homebuyer programs have 80% or 100% AMI cut-offs, but Habitat for Humanity of Greater Charlottesville reaches households at 25% AMI.

Morrison said that those in the middle of these groups, at around 40% AMI, often qualify for few programs. And although those who make less than 30% AMI are the intended recipients of many programs, the resources are often not there to cover that group adequately.

It’s this debate about who is receiving resources and who is being left out that drives public housing resident Joy Johnson to continually ask rooms of affordable housing experts, activists and providers, “Affordable for whom?”

Johnson helped found Charlottesville’s Public Housing Association of Residents in 1998 and has remained a key voice in housing conversations since then.

“Equity [and wealth] in this town has not risen for some people, but it has for others,” Johnson said. “When you say affordability, the affordability is not for everybody.”

HUD defined a low-income family of four as making less than $68,250 a year in 2018. That number is not close to the incomes Johnson sees among her neighbors, around half of whom make less than $8,600 a year, according to Morrison’s assessment.

This lowest income tier is the group most disproportionately affected by the housing crisis. Public housing residents and those with subsidized rents are the lucky ones in this group; a family in the 30% AMI income tier has a roughly 70% chance of paying more than they can afford for housing.

No other options

Yolanda Adams’ training as a nurse became important for her family’s health a few years ago when her newborn son was diagnosed with a chronic lung disease, she said.

Adams put her job on hold to take care of her son. She said that she could not take her newborn home to Westhaven public housing because of the poor conditions there. She was able to get the hospital to recommend her transfer to a better apartment in the South First Street public housing neighborhood, she said.

At 2½ years old, Adams’ son is just now able to live independently from medical equipment like feeding tubes and a ventilator. When he starts the city’s preschool program in the fall, Adams will be able to get back to work, she said.

Adams relies on a roughly $9,000 annual income that her son’s disability makes her eligible for. She estimated that her income was around $15,000 a year when she took on private cases as a Certified Nursing Assistant.

Neither income is sufficient to rent or own a home without subsidies.

The year before Adams moved into public housing, she lived on 7½ Street in Fifeville, she said. She only could afford a one-bedroom apartment for herself and her two kids at the time.

Morrison said that affordable rents for Adams’ peers do not even cover the cost of operating an apartment building, much less return a developer’s investment in new construction. Affordability is almost entirely dependent on federal subsidies.

Johnson has been looking at the problem of how to pay for redevelopment of Charlottesville’s public housing neighborhoods. So far, the redevelopment team has put together a combination of federal subsidies, tax credits and private donations to start reconstruction.

Adams said that she does not want to live in public housing for the rest of her life, but it is hard to see a way out of her current situation. She said that it is hard to save money and that savings get calculated into her monthly rent.

Adams said that she tries to save $50 a month these days, paying for her rent and car insurance out of her monthly check and using food stamps for groceries. She said that neither of her incomes have been enough for anyone to live on.

“There’s not much that you can do except wait for the next check to come,” Adams said.

PHAR and the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority have been working to create a career development program for residents and their neighbors.

This program would prioritize using housing authority resources to train low-income area residents and hire resident-led contractors. Chicago-based GMA Construction Group, which was chosen to start redevelopment, specializes in these Section 3 programs.

Meanwhile, Adams has found one possible path to homeownership through Habitat for Humanity. She is checking whether she qualifies to build and purchase her own home through the nonprofit.

ould prioritize using housing authority resources to train low-income area residents and hire resident-led contractors. Chicago-based GMA Construction Group, which was chosen to start redevelopment, specializes in these Section 3 programs.Meanwhile, Adams has found one possible path to homeownership through Habitat for Humanity. She is checking whether she qualifies to build and purchase her own home through the nonprofit.

Squeezed at the top

More than ⅔ of those struggling with housing costs in the Charlottesville area make more than 30% of area median income. Some of the people struggling even make more than the median income.

Families making between 50% and 80% of AMI are the second largest group squeezed by housing costs in the area, according to Morrison’s calculations.

Chef Brinson’s family income currently is around the cutoff between this income tier and median income, he said.

Brinson moved from San Francisco to Charlottesville. In comparison to rents there, the prices in Charlottesville are doable, he said. The relative affordability allowed him to gather his savings from previous high-paying jobs to start his business.

Brinson’s wife, Margaret, who works remotely for a San Francisco doctor’s office, is the family’s main income earner right now.

“When you have a business, your revenues and your net are very different. Revenues-wise, my company is doing extremely well, but what Antwon brings home isn’t much. I bring home enough to pay the bills,” Brinson said.

Brinson said that he expects to have a much higher salary next year, and he is planning to buy a house. The couple’s budget is $250,000 to $350,000.

They probably will buy in Scottsville, Brinson said. The couple is happy with reviews of most of the schools there, and Brinson said he is not worried about the time spent driving since he travels often during work hours.

Brinson said that if costs were different, the couple probably would like to live closer into town but still out of the reach of the homeownership associations in subdivisions. Brinson already has planned his dream home thoroughly, which would have large windows, state-of-the-art kitchen equipment and a pool that could be converted into a place to skateboard when empty.

The fewer grocery store options in Scottsville versus the Forest Lakes area will be a sacrifice, Brinson said, but they would trade that for more living space and the chance to hit his goal of owning a home before age 40.

Brinson said that he sees even well-paid peers struggling with the cost of housing in the area but rarely hears that story told.

“I don’t say anything because there’s someone else out there worse off than me,” Brinson said.

Brinson said he hears many of these stories as he mentors students through Culinary Concepts.

“I think that the most important thing is that it’s a problem, and it affects people on different levels. Being able to recognize it for what it is gives you an opportunity to address it as a whole.”

This article was updated on Jan. 21. The Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority does not include first or second cars in the calculation of residents’ rents.